Reimagining Sufi Poetics in South Asia:

The Literary Writings of Ḥasan Sijzī Dihlavī (1253–c.1337)

Pranav Prakash

Abstract of my PhD Dissertation | Defended in May 2020 | University of Iowa

The Literary Writings of Ḥasan Sijzī Dihlavī (1253–c.1337)

Pranav Prakash

Abstract of my PhD Dissertation | Defended in May 2020 | University of Iowa

My dissertation seeks to understand why and how an early modern Indian poet survived in the cultural memory of South Asian and Persian societies. Under what circumstances were his life and literary oeuvre remembered, appreciated and/or forgotten? These questions are posed with the aim of elucidating the contexts of reception that shape the development of literatures and literary histories in South Asia and the wider Persian world. To that end, my dissertation explores the life, works and legacy of Ḥasan Sijzī Dihlavī, an Indian poet who wrote exclusively in Persian and whose writings circulated in all parts of the wider Persian world—from Daulatabad in India to Samarqand in Uzbekistan and Shiraz in Iran. To document the reception history of Ḥasan's biographies and literary works, I pursued archival research in different parts of India, Iran, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Jordan, England, France and the US. At the culmination of my archival research, I came across some two hundred new manuscripts—as opposed to twenty previously known ones—containing his works. Additionally, I conducted ethno-historiographic research on his living legacy in north India, Rajasthan and the Deccan region. Apart from shedding new light on his biography, Sufi poetics and cultural reception, these archival data and ethnographic fieldnotes allow my dissertation to address some of the cardinal issues in South Asian literary history and historiography.

Contemporary historiography is fundamentally concerned about the nature and limits of the intercultural interactions among Muslims and other religious communities in early modern India and their formative role in the making of modern South Asia. To that end, most historical narratives of the longue durée of intercultural transactions in the Indian subcontinent rely heavily on courtly documents and elite artifacts in their attempt to elucidate the “conquest” of one regional or religious community by a dominant “other” and/or to delineate the alleged “encounter” among competing intellectual traditions and philosophical schools. These polarized narratives undervalue the ethos and subjectivity of the vast majority of the Indian populace who did not necessarily view themselves as agents of political domination, cultural conquest, religious confrontation and/or elite contestation. Against this backdrop, the literary writings of Ḥasan illuminate the communal ethos of people of diverse cultural, social and religious backgrounds in early modern India. As a poet, he frequently participated in cultural gatherings, literary circles, religious festivals and social events. Apropos to his close association with both royal courts and Sufi khānqāhs, he was able to transform courtly literary genres and adapt them to religious, mystical, ethical and even secular themes relevant to a larger and more diverse audience in India and abroad. As attested by the reception history of his literary works and manuscripts, his literary oeuvre became immensely popular among Indians and left a deep impact on the literary traditions and Sufi discourses of the wider Persianate world.

|

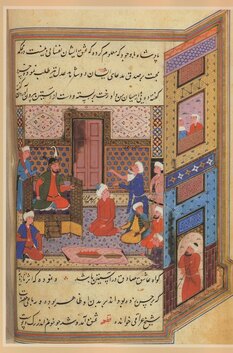

Amīr Khusrau showing wound marks to Sulṭān Shāhid, after the latter flogged and imprisoned Ḥasan on the charge of meeting Khusrau against his will (Majālis al-ʿUshshāq [Gatherings of Lovers], Ms. Persan 1150, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

|

Most historical sources acknowledge that Ḥasan and his dear friend Amīr Khusrau (d. 1325) played a foundational role in the spread of Sufi poetry and Persian genres in early modern South Asia. Whereas numerous studies have explored Khusrau’s poetry, a comprehensive exposition of Ḥasan’s literary writings and Sufi poetics is still unavailable. In the absence of a detailed study of his poetry, most scholarly depictions of the literary and religious history of early modern India, particularly of the Ghaznavid era (c. 960-1190) and Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526), cast Ḥasan merely in a supporting role to his illustrious contemporaries—sometimes as a minor accomplice to Khusrau; sometimes as an aspiring pupil of the Sufi saint Shaykh Niẓāmuddīn ʿAwliyāʾ (d. 1325); or, sometimes as a lesser stylist inspired by Saʿdī (d. c. 1291). Although Khusrau affirmed that the “divine secrets” of his poetry emanated “the fragrance of Ḥasan” and successive generations of poets – for instance, Ḥāfiẓ of Shīrāz (d. 1389/90), Khvājū Kirmānī (d. c. 1349), Kamāl Khujandī (d. 1400), Zayn al-Dīn Vāṣifī (d. c. 1551-56), Ẓamīrī of Iṣfahan (d. 1565/1566) and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Mushfiqī (d. 1588) – admired his poetry, contemporary scholarship remains mostly oblivious of his literary craft, creative innovation and poetic vision. My dissertation amends this academic oversight by offering a critical appraisal of his literary works and their reception history.

Literary historians grapple with the issue of how Persian literary genres—originally conceived in Iranian and Central Asian cultural milieux—were made amenable to the diverse literary tastes, cultural values, and religious worldviews of Indian audience. Ḥasan inaugurated and pioneered a tradition of literary experimentation and innovation that led to the popularization of Persian genres in South Asia. His ʿIshqnāma (The Book of Love) is the first Persian mas̱navī to recount a Rājasthānī folktale and adapt Indic metaphors. Likewise, he reimagined the stylistic and semantic textures of several Persian genres, particularly ghazal, qāṣida, rubāʿī, tarjīʿband, tarkībband, qitaʿ and malfūẓ, for both local and global audiences. |

My unraveling of the creative imagination and Sufi worldview of Ḥasan is ultimately channeled toward exploring how and why his poetics resonated in a wide variety of historical, cultural, religious and political settings. Literary critics, anthropologists and sociologists have offered critical reflections on the notion of “resonance,” particularly on its relevance for affirming the primacy of auditory experiences over literate practices, emotions over rational faculties, democratic values over elite judgments, and a sense of belongingness in human interactions and cultural history. Resonance thus foregrounds and elaborates the dynamic of social connection and intimacy in a pluralistic cultural milieu. It is therefore a primary mode of historical reception and transmission which, in turn, are the raison d’être of literary history. This ebb and flow in the history of cultural recognition, literary appreciation and religious canonization characterizes much of the life and works of Ḥasan. Whereas the echo of his poetics was heard loud and clear in certain regional genres (e.g., Avadhī Sufi premākhyāns and Hindūstānī ghazals) and manuscript traditions (e.g., Persian bayāż and Rājasthānī guṭkhā), its resonance was considerably subdued in modern print culture, orientalist discourses and nationalist historiography. While the decline of Persian in South Asia adversely affected the reception of his Fārsī songs, his poetics held their sway among Sufi saints and Muslim intellectuals. Moreover, his tomb in Khuldabad emerged as an active site of pilgrimage and worship, often attracting visitors suffering from speech disorders and learning disabilities. They all believe that Ḥasan’s “sweet speech” cures the illness of ineloquence. The resonance of his Sufi poetics thus affirms its relevance for the literary and religious history of South Asia.

A Panoramic View of Ḥasan's Tomb in Khuldabad | Photographed in August 2017 | © 2024 Pranav Prakash